Page 152 - Bruce Ellig - The Complete Guide to Executive Compensation (2007)

P. 152

138 The Complete Guide to Executive Compensation

the Vietnam War. Listed also is the 1993 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act; although it

was primarily a tax act, it did curtail the amount of pay that would be tax deductible unless

performance based. More will be said later about this law.

Tax Considerations. Congress periodically passes legislation that amends the IRC, stipu-

lating what is taxable and at what rate. It also describes what may be excluded from income

and what expenses may be deducted from income. The latter is a tax deduction and differs

from a tax credit in that a credit may be directly applied to reduce taxes due. The general rule

is that compensation (whether in cash or stock) received by the executive is taxable when received, and

the company has a tax deduction at that time for the same amount. Exceptions to this rule are the

capital gains tax and alternative minimum tax, which are not tax deductible to the company.

Essentially there are four levels of tax information. First is the Internal Revenue Code,

which is the collection of tax laws passed by Congress. Next are the income tax regulations

(ITR), written by the Internal Revenue Service and interpreting the IRC. Third are the

Revenue Rulings made by the IRS to interpret the IRC and/or the ITR. And finally, there are

private letter rulings, which interpret the IRC/ITR Revenue Rulings for a specific company.

History of Taxation. It is hard to believe that income taxes have not always been a part of the

United States economy. Actually, we almost made the first 100 years without such a system by

financing the government through the sale of lands and the collection of duties and tariffs. But

in 1861, an income tax was introduced to help finance the costs of the Civil War. It was removed

in 1872. In 1894, Congress again imposed an income tax, but the U.S. Supreme Court struck

it down in 1895, citing a conflict with Article 1, Section 9 of the Constitution, which stated,

“Taxes must be in direct proportion to the census or enumeration.” That roadblock was

removed in 1913 following passage of the 16th Amendment. It states, “The Congress shall

have the power to lay and collect taxes on incomes from whatever source derived, without

apportionment among the several states, and without regard to any census or enumeration.”

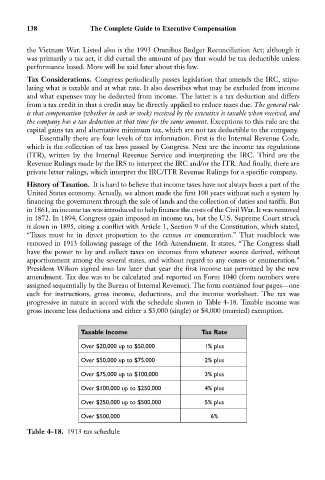

President Wilson signed into law later that year the first income tax permitted by the new

amendment. Tax due was to be calculated and reported on Form 1040 (form numbers were

assigned sequentially by the Bureau of Internal Revenue). The form contained four pages—one

each for instructions, gross income, deductions, and the income worksheet. The tax was

progressive in nature in accord with the schedule shown in Table 4-18. Taxable income was

gross income less deductions and either a $3,000 (single) or $4,000 (married) exemption.

Taxable Income Tax Rate

Over $20,000 up to $50,000 1% plus

Over $50,000 up to $75,000 2% plus

Over $75,000 up to $100,000 3% plus

Over $100,000 up to $250,000 4% plus

Over $250,000 up to $500,000 5% plus

Over $500,000 6%

Table 4-18. 1913 tax schedule