Page 78 - Air pollution and greenhouse gases from basic concepts to engineering applications for air emission control

P. 78

52 2 Basic Properties of Gases

formed above the liquid-gas interface reaches its dynamic equilibrium, the rate at

which liquid evaporates is equal to the rate that the gas is condensing back to liquid

phase. This is called the vapor pressure. All liquids have vapor pressure, and the

vapor pressure is constant regardless of absolute amount of the liquid substance.

The vapor pressure of the solution will generally decrease as solute dissolves in

the liquid phase. As additional solute molecules fill the gaps between the solvent

molecules and take up space, less of the liquid molecules will be on the surface and

less will be able to break free to join the vapor.

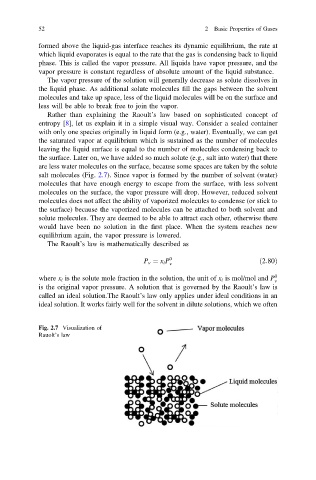

Rather than explaining the Raoult’s law based on sophisticated concept of

entropy [8], let us explain it in a simple visual way. Consider a sealed container

with only one species originally in liquid form (e.g., water). Eventually, we can get

the saturated vapor at equilibrium which is sustained as the number of molecules

leaving the liquid surface is equal to the number of molecules condensing back to

the surface. Later on, we have added so much solute (e.g., salt into water) that there

are less water molecules on the surface, because some spaces are taken by the solute

salt molecules (Fig. 2.7). Since vapor is formed by the number of solvent (water)

molecules that have enough energy to escape from the surface, with less solvent

molecules on the surface, the vapor pressure will drop. However, reduced solvent

molecules does not affect the ability of vaporized molecules to condense (or stick to

the surface) because the vaporized molecules can be attached to both solvent and

solute molecules. They are deemed to be able to attract each other, otherwise there

would have been no solution in the first place. When the system reaches new

equilibrium again, the vapor pressure is lowered.

The Raoult’s law is mathematically described as

P v ¼ x i P 0 ð2:80Þ

v

where x i is the solute mole fraction in the solution, the unit of x i is mol/mol and P 0

v

is the original vapor pressure. A solution that is governed by the Raoult’s law is

called an ideal solution.The Raoult’s law only applies under ideal conditions in an

ideal solution. It works fairly well for the solvent in dilute solutions, which we often

Fig. 2.7 Visualization of

Rauolt’s law