Page 103 - Earth's Climate Past and Future

P. 103

CHAPTER 4 • Plate Tectonics and Long-Term Climate 79

heavy precipitation, and glacial erosion) combine to

generate a continual supply of fresh, finely ground rock

100%

debris for weathering. Some of this weathering occurs

on the steep upper slopes of exposed high terrain even

in the absence of much vegetation or soil cover. Much

0˚ of it occurs in basins lower in the mountains, where

soils and vegetation have gained a tenuous foothold,

and yet the supply of fresh unweathered rock debris

Andes from higher-elevation streams and rivers is continuous.

80%

The absence of obvious visible chemical weathering

in the Andes has two explanations. First, chemical weath-

Lowlands

20% ering products such as clays are continually overwhelmed

by the much larger supply of physically fragmented

Eastern Andes debris cascading down the steep slopes. Second, the fine

clays and other products of weathering are continually

removed from steep slopes and carried to the ocean by

streams and rivers.

30˚S The Amazon Basin studies confirm that the rate of

Western Andes

chemical weathering is rapid in the Andes and presum-

ably in many of Earth’s other high-elevation regions as

well, even though the visible effects of chemical weath-

ering are not apparent. These studies also show that

some warm, wet, vegetated regions may be places of

surprisingly slow chemical weathering.

60˚W

4-12 Weathering: Both a Climate Forcing and a

90˚W Feedback?

The original uplift weathering hypothesis left an

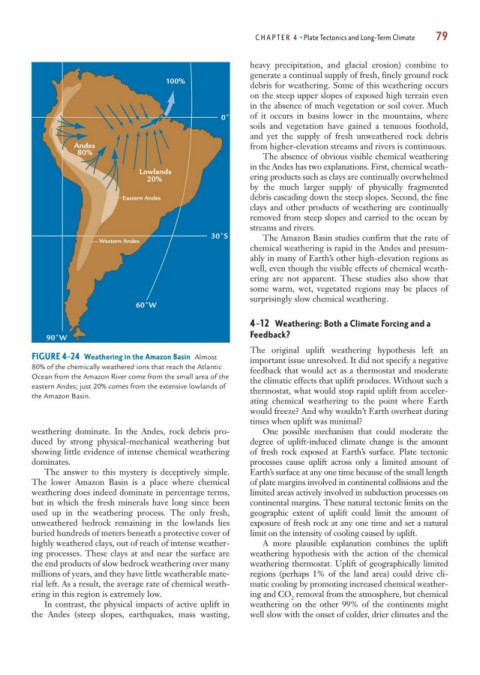

FIGURE 4-24 Weathering in the Amazon Basin Almost important issue unresolved. It did not specify a negative

80% of the chemically weathered ions that reach the Atlantic feedback that would act as a thermostat and moderate

Ocean from the Amazon River come from the small area of the the climatic effects that uplift produces. Without such a

eastern Andes; just 20% comes from the extensive lowlands of thermostat, what would stop rapid uplift from acceler-

the Amazon Basin.

ating chemical weathering to the point where Earth

would freeze? And why wouldn’t Earth overheat during

times when uplift was minimal?

weathering dominate. In the Andes, rock debris pro- One possible mechanism that could moderate the

duced by strong physical-mechanical weathering but degree of uplift-induced climate change is the amount

showing little evidence of intense chemical weathering of fresh rock exposed at Earth’s surface. Plate tectonic

dominates. processes cause uplift across only a limited amount of

The answer to this mystery is deceptively simple. Earth’s surface at any one time because of the small length

The lower Amazon Basin is a place where chemical of plate margins involved in continental collisions and the

weathering does indeed dominate in percentage terms, limited areas actively involved in subduction processes on

but in which the fresh minerals have long since been continental margins. These natural tectonic limits on the

used up in the weathering process. The only fresh, geographic extent of uplift could limit the amount of

unweathered bedrock remaining in the lowlands lies exposure of fresh rock at any one time and set a natural

buried hundreds of meters beneath a protective cover of limit on the intensity of cooling caused by uplift.

highly weathered clays, out of reach of intense weather- A more plausible explanation combines the uplift

ing processes. These clays at and near the surface are weathering hypothesis with the action of the chemical

the end products of slow bedrock weathering over many weathering thermostat. Uplift of geographically limited

millions of years, and they have little weatherable mate- regions (perhaps 1% of the land area) could drive cli-

rial left. As a result, the average rate of chemical weath- matic cooling by promoting increased chemical weather-

ering in this region is extremely low. ing and CO removal from the atmosphere, but chemical

2

In contrast, the physical impacts of active uplift in weathering on the other 99% of the continents might

the Andes (steep slopes, earthquakes, mass wasting, well slow with the onset of colder, drier climates and the