Page 53 - Earth's Climate Past and Future

P. 53

CHAPTER 2 • Climate Archives, Data, and Models 29

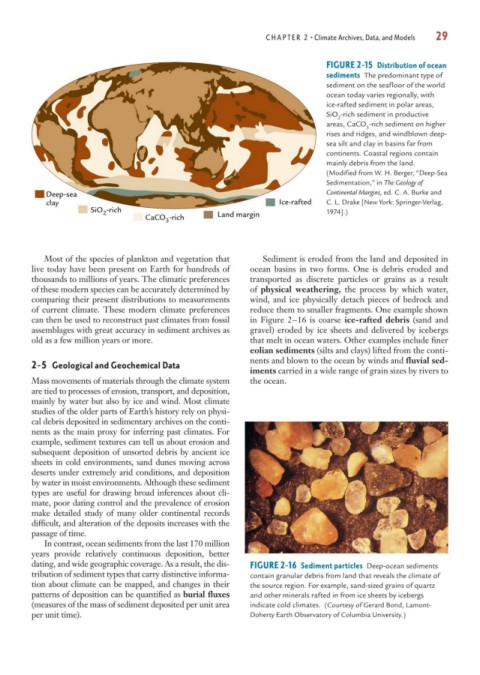

FIGURE 2-15 Distribution of ocean

sediments The predominant type of

sediment on the seafloor of the world

ocean today varies regionally, with

ice-rafted sediment in polar areas,

SiO -rich sediment in productive

2

areas, CaCO -rich sediment on higher

3

rises and ridges, and windblown deep-

sea silt and clay in basins far from

continents. Coastal regions contain

mainly debris from the land.

(Modified from W. H. Berger, “Deep-Sea

Sedimentation,” in The Geology of

Deep-sea Continental Margins, ed. C. A. Burke and

clay Ice-rafted C. L. Drake [New York: Springer-Verlag,

SiO -rich 1974].)

2

CaCO -rich Land margin

3

Most of the species of plankton and vegetation that Sediment is eroded from the land and deposited in

live today have been present on Earth for hundreds of ocean basins in two forms. One is debris eroded and

thousands to millions of years. The climatic preferences transported as discrete particles or grains as a result

of these modern species can be accurately determined by of physical weathering, the process by which water,

comparing their present distributions to measurements wind, and ice physically detach pieces of bedrock and

of current climate. These modern climate preferences reduce them to smaller fragments. One example shown

can then be used to reconstruct past climates from fossil in Figure 2–16 is coarse ice-rafted debris (sand and

assemblages with great accuracy in sediment archives as gravel) eroded by ice sheets and delivered by icebergs

old as a few million years or more. that melt in ocean waters. Other examples include finer

eolian sediments (silts and clays) lifted from the conti-

nents and blown to the ocean by winds and fluvial sed-

2-5 Geological and Geochemical Data

iments carried in a wide range of grain sizes by rivers to

Mass movements of materials through the climate system the ocean.

are tied to processes of erosion, transport, and deposition,

mainly by water but also by ice and wind. Most climate

studies of the older parts of Earth’s history rely on physi-

cal debris deposited in sedimentary archives on the conti-

nents as the main proxy for inferring past climates. For

example, sediment textures can tell us about erosion and

subsequent deposition of unsorted debris by ancient ice

sheets in cold environments, sand dunes moving across

deserts under extremely arid conditions, and deposition

by water in moist environments. Although these sediment

types are useful for drawing broad inferences about cli-

mate, poor dating control and the prevalence of erosion

make detailed study of many older continental records

difficult, and alteration of the deposits increases with the

passage of time.

In contrast, ocean sediments from the last 170 million

years provide relatively continuous deposition, better

dating, and wide geographic coverage. As a result, the dis- FIGURE 2-16 Sediment particles Deep-ocean sediments

tribution of sediment types that carry distinctive informa- contain granular debris from land that reveals the climate of

tion about climate can be mapped, and changes in their the source region. For example, sand-sized grains of quartz

patterns of deposition can be quantified as burial fluxes and other minerals rafted in from ice sheets by icebergs

(measures of the mass of sediment deposited per unit area indicate cold climates. (Courtesy of Gerard Bond, Lamont-

per unit time). Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University.)