Page 180 - Fair, Geyer, and Okun's Water and wastewater engineering : water supply and wastewater removal

P. 180

JWCL344_ch04_118-153.qxd 8/2/10 9:18 PM Page 142

142 Chapter 4 Quantities of Water and Wastewater Flows

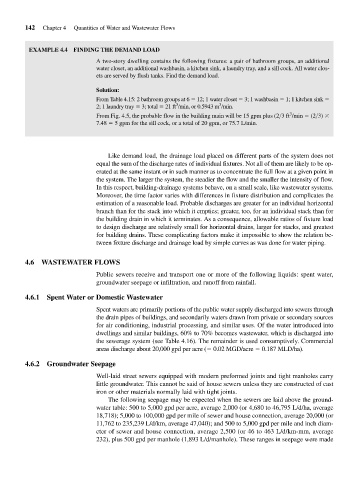

EXAMPLE 4.4 FINDING THE DEMAND LOAD

A two-story dwelling contains the following fixtures: a pair of bathroom groups, an additional

water closet, an additional washbasin, a kitchen sink, a laundry tray, and a sill cock. All water clos-

ets are served by flush tanks. Find the demand load.

Solution:

From Table 4.15: 2 bathroom groups at 6 12; 1 water closet 3; 1 washbasin 1; 1 kitchen sink

3

3

2; 1 laundry tray 3; total 21 ft /min, or 0.5943 m /min.

3

From Fig. 4.5, the probable flow in the building main will be 15 gpm plus (2>3 ft /min (2>3)

7.48 5 gpm for the sill cock, or a total of 20 gpm, or 75.7 L/min.

Like demand load, the drainage load placed on different parts of the system does not

equal the sum of the discharge rates of individual fixtures. Not all of them are likely to be op-

erated at the same instant or in such manner as to concentrate the full flow at a given point in

the system. The larger the system, the steadier the flow and the smaller the intensity of flow.

In this respect, building-drainage systems behave, on a small scale, like wastewater systems.

Moreover, the time factor varies with differences in fixture distribution and complicates the

estimation of a reasonable load. Probable discharges are greater for an individual horizontal

branch than for the stack into which it empties; greater, too, for an individual stack than for

the building drain in which it terminates. As a consequence, allowable ratios of fixture load

to design discharge are relatively small for horizontal drains, larger for stacks, and greatest

for building drains. These complicating factors make it impossible to show the relation be-

tween fixture discharge and drainage load by simple curves as was done for water piping.

4.6 WASTEWATER FLOWS

Public sewers receive and transport one or more of the following liquids: spent water,

groundwater seepage or infiltration, and runoff from rainfall.

4.6.1 Spent Water or Domestic Wastewater

Spent waters are primarily portions of the public water supply discharged into sewers through

the drain pipes of buildings, and secondarily waters drawn from private or secondary sources

for air conditioning, industrial processing, and similar uses. Of the water introduced into

dwellings and similar buildings, 60% to 70% becomes wastewater, which is discharged into

the sewerage system (see Table 4.16). The remainder is used consumptively. Commercial

areas discharge about 20,000 gpd per acre ( 0.02 MGD/acre 0.187 MLD/ha).

4.6.2 Groundwater Seepage

Well-laid street sewers equipped with modern preformed joints and tight manholes carry

little groundwater. This cannot be said of house sewers unless they are constructed of cast

iron or other materials normally laid with tight joints.

The following seepage may be expected when the sewers are laid above the ground-

water table: 500 to 5,000 gpd per acre, average 2,000 (or 4,680 to 46,795 L/d/ha, average

18,718); 5,000 to 100,000 gpd per mile of sewer and house connection, average 20,000 (or

11,762 to 235,239 L/d/km, average 47,040); and 500 to 5,000 gpd per mile and inch diam-

eter of sewer and house connection, average 2,500 (or 46 to 463 L/d/km-mm, average

232), plus 500 gpd per manhole (1,893 L/d/manhole). These ranges in seepage were made