Page 234 - Microtectonics

P. 234

224 7 · Porphyroblasts and Reaction Rims

7.7 7.7 diffusion rate and crystal growth rate due to changing

Crystallographically Determined Inclusion Patterns metamorphic conditions, possibly related to a growth in-

terval. However, it may also be due to a change in the por-

Passive inclusion as described in Sects. 7.3–7.5 is not the phyroblast-forming reactions, if a new reaction becomes

only process that controls the inclusion of foreign mat- active which consumes the mineral that forms inclusions.

ter in a porphyroblast. In some porphyroblasts the dis-

tribution and shape of inclusion density pattern are as-

sociated with crystal habit (Figs. 7.46–7.49). Character-

istic microstructures are textural sector zoning and re-

entrant zones (Fig. 7.50, ×Video 7.50; Rice and Mitchell

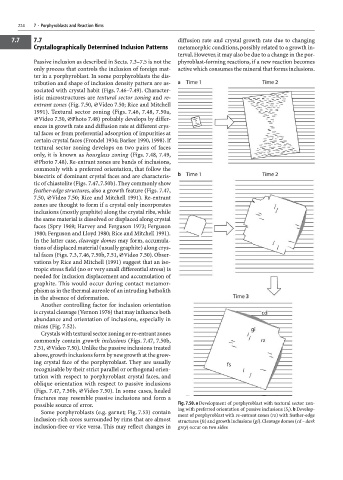

1991). Textural sector zoning (Figs. 7.46, 7.48, 7.50a,

×Video 7.50, ×Photo 7.48) probably develops by differ-

ences in growth rate and diffusion rate at different crys-

tal faces or from preferential adsorption of impurities at

certain crystal faces (Frondel 1934; Barker 1990, 1998). If

textural sector zoning develops on two pairs of faces

only, it is known as hourglass zoning (Figs. 7.48, 7.49,

×Photo 7.48). Re-entrant zones are bands of inclusions,

commonly with a preferred orientation, that follow the

bisectrix of dominant crystal faces and are characteris-

tic of chiastolite (Figs. 7.47, 7.50b). They commonly show

feather-edge structures, also a growth feature (Figs. 7.47,

7.50, ×Video 7.50; Rice and Mitchell 1991). Re-entrant

zones are thought to form if a crystal only incorporates

inclusions (mostly graphite) along the crystal ribs, while

the same material is dissolved or displaced along crystal

faces (Spry 1969; Harvey and Ferguson 1973; Ferguson

1980; Ferguson and Lloyd 1980; Rice and Mitchell 1991).

In the latter case, cleavage domes may form, accumula-

tions of displaced material (usually graphite) along crys-

tal faces (Figs. 7.3, 7.46, 7.50b, 7.51, ×Video 7.50). Obser-

vations by Rice and Mitchell (1991) suggest that an iso-

tropic stress field (no or very small differential stress) is

needed for inclusion displacement and accumulation of

graphite. This would occur during contact metamor-

phism as in the thermal aureole of an intruding batholith

in the absence of deformation.

Another controlling factor for inclusion orientation

is crystal cleavage (Vernon 1976) that may influence both

abundance and orientation of inclusions, especially in

micas (Fig. 7.52).

Crystals with textural sector zoning or re-entrant zones

commonly contain growth inclusions (Figs. 7.47, 7.50b,

7.51, ×Video 7.50). Unlike the passive inclusions treated

above, growth inclusions form by new growth at the grow-

ing crystal face of the porphyroblast. They are usually

recognisable by their strict parallel or orthogonal orien-

tation with respect to porphyroblast crystal faces, and

oblique orientation with respect to passive inclusions

(Figs. 7.47, 7.50b, ×Video 7.50). In some cases, healed

fractures may resemble passive inclusions and form a

possible source of error. Fig. 7.50. a Development of porphyroblast with textural sector zon-

Some porphyroblasts (e.g. garnet; Fig. 7.53) contain ing with preferred orientation of passive inclusions (S ). b Develop-

i

ment of porphyroblast with re-entrant zones (rz) with feather-edge

inclusion-rich cores surrounded by rims that are almost structures (fs) and growth inclusions (gi). Cleavage domes (cd – dark

inclusion-free or vice versa. This may reflect changes in grey) occur on two sides