Page 432 - The Mechatronics Handbook

P. 432

0066_Frame_C19 Page 54 Wednesday, January 9, 2002 5:27 PM

variations in magnetic properties of typical shaft surfaces limit their accuracy. Solenoidal designs, illus-

trated in Fig. 19.47(c), avoid this pitfall by effectively averaging these variations. Type 2 transducers are

generally constructed with a ring of magnetoelastically active material rigidly attached to the shaft. The

ring is magnetized during manufacture of the transducer, usually with each axial half polarized in an

opposite circumferential direction as indicated by the solid arrows in Fig. 19.47(d) [11]. When torque is

applied, the magnetizations tilt into helical directions (dashed arrows), causing magnetic poles to develop

at the central domain wall and (of opposite polarity) at the ring end faces. Torque is determined from

the output signal of one or more magnetic field sensors (e.g., Hall effect, magnetoresistive, or flux gate

devices) mounted so as to sense the intensity and polarity of the magnetic field that arises in the space

near the ring.

Torque Transducer Construction, Operation, and Application

Although a torque sensing region can be created directly on a desired shaft, it is more usual to install a

preassembled modular torque transducer into the driveline. Transducers of this type are available with

capacities from 0.001 to 200,000 Nm. Operating principle descriptions and detailed installation and

operating instructions can be found in the catalogs and literature of the various manufacturers [12–20].

Tradenames often identify a specific type of transducers; for example, Torquemeters [13] refers to a family

of noncontact strain gage models; Torkducer®[18] identifies a line of Type 1 magnetoelastic transducers;

Torqstar TM [12] identifies a line of Type 2 magnetoelastic transducers; Torquetronic [16] is a class of

transducers using wrap-around twist angle sensors; and TorXimitor TM [20] identifies optoelectronic-

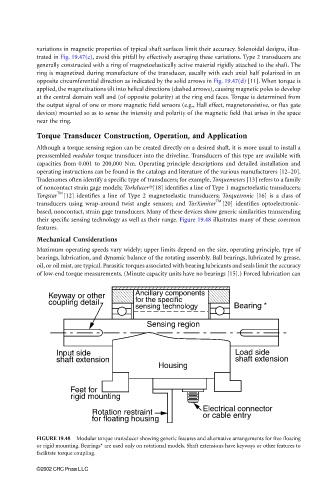

based, noncontact, strain gage transducers. Many of these devices show generic similarities transcending

their specific sensing technology as well as their range. Figure 19.48 illustrates many of these common

features.

Mechanical Considerations

Maximum operating speeds vary widely; upper limits depend on the size, operating principle, type of

bearings, lubrication, and dynamic balance of the rotating assembly. Ball bearings, lubricated by grease,

oil, or oil mist, are typical. Parasitic torques associated with bearing lubricants and seals limit the accuracy

of low-end torque measurements. (Minute capacity units have no bearings [15].) Forced lubrication can

Keyway or other Ancillary components

coupling detail for the specific

sensing technology Bearing *

Sensing region

Input side Load side

shaft extension shaft extension

Housing

Feet for

rigid mounting

Electrical connector

Rotation restraint or cable entry

for floating housing

FIGURE 19.48 Modular torque transducer showing generic features and alternative arrangements for free floating

or rigid mounting. Bearings* are used only on rotational models. Shaft extensions have keyways or other features to

facilitate torque coupling.

©2002 CRC Press LLC