Page 196 - Theory and Design of Air Cushion Craft

P. 196

Dynamic stability, plough-in and overturning 179

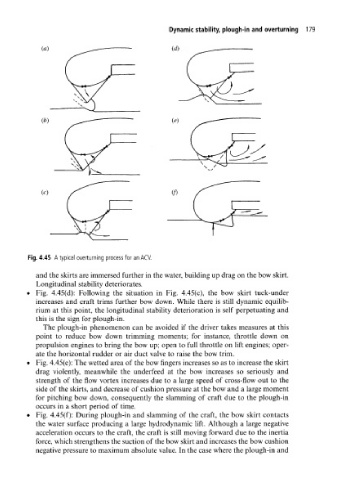

Fig. 4.45 A typical overturning process for an ACV.

and the skirts are immersed further in the water, building up drag on the bow skirt.

Longitudinal stability deteriorates.

• Fig. 4.45(d): Following the situation in Fig. 4.45(c), the bow skirt tuck-under

increases and craft trims further bow down. While there is still dynamic equilib-

rium at this point, the longitudinal stability deterioration is self perpetuating and

this is the sign for plough-in.

The plough-in phenomenon can be avoided if the driver takes measures at this

point to reduce bow down trimming moments; for instance, throttle down on

propulsion engines to bring the bow up; open to full throttle on lift engines; oper-

ate the horizontal rudder or air duct valve to raise the bow trim.

• Fig. 4.45(e): The wetted area of the bow fingers increases so as to increase the skirt

drag violently, meanwhile the underfeed at the bow increases so seriously and

strength of the flow vortex increases due to a large speed of cross-flow out to the

side of the skirts, and decrease of cushion pressure at the bow and a large moment

for pitching bow down, consequently the slamming of craft due to the plough-in

occurs in a short period of time.

• Fig. 4.45(f): During plough-in and slamming of the craft, the bow skirt contacts

the water surface producing a large hydrodynamic lift. Although a large negative

acceleration occurs to the craft, the craft is still moving forward due to the inertia

force, which strengthens the suction of the bow skirt and increases the bow cushion

negative pressure to maximum absolute value. In the case where the plough-in and