Page 202 - Computational Retinal Image Analysis

P. 202

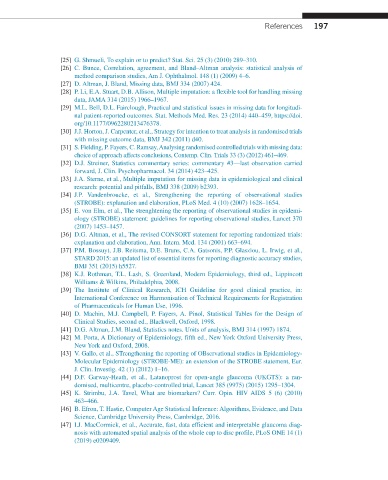

References 197

[25] G. Shmueli, To explain or to predict? Stat. Sci. 25 (3) (2010) 289–310.

[26] C. Bunce, Correlation, agreement, and Bland–Altman analysis: statistical analysis of

method comparison studies, Am J. Ophthalmol. 148 (1) (2009) 4–6.

[27] D. Altman, J. Bland, Missing data, BMJ 334 (2007) 424.

[28] P. Li, E.A. Stuart, D.B. Allison, Multiple imputation: a flexible tool for handling missing

data, JAMA 314 (2015) 1966–1967.

[29] M.L. Bell, D.L. Fairclough, Practical and statistical issues in missing data for longitudi-

nal patient-reported outcomes. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 23 (2014) 440–459, https://doi.

org/10.1177/0962280213476378.

[30] J.J. Horton, J. Carpenter, et al., Strategy for intention to treat analysis in randomised trials

with missing outcome data, BMJ 342 (2011) d40.

[31] S. Fielding, P. Fayers, C. Ramsay, Analysing randomised controlled trials with missing data:

choice of approach affects conclusions, Contemp. Clin. Trials 33 (3) (2012) 461–469.

[32] D.J. Streiner, Statistics commentary series: commentary #3—last observation carried

forward, J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 34 (2014) 423–425.

[33] J.A. Sterne, et al., Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical

research: potential and pitfalls, BMJ 338 (2009) b2393.

[34] J.P. Vandenbroucke, et al., Strengthening the reporting of observational studies

(STROBE): explanation and elaboration, PLoS Med. 4 (10) (2007) 1628–1654.

[35] E. von Elm, et al., The strenghtening the reporting of observational studies in epidemi-

ology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies, Lancet 370

(2007) 1453–1457.

[36] D.G. Altman, et al., The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials:

explanation and elaboration, Ann. Intern. Med. 134 (2001) 663–694.

[37] P.M. Bossuyt, J.B. Reitsma, D.E. Bruns, C.A. Gatsonis, P.P. Glasziou, L. Irwig, et al.,

STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies,

BMJ 351 (2015) h5527.

[38] K.J. Rothman, T.L. Lash, S. Greenland, Modern Epidemiology, third ed., Lippincott

Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2008.

[39] The Institute of Clinical Research, ICH Guideline for good clinical practice, in:

International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration

of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, 1996.

[40] D. Machin, M.J. Campbell, P. Fayers, A. Pinol, Statistical Tables for the Design of

Clinical Studies, second ed., Blackwell, Oxford, 1998.

[41] D.G. Altman, J.M. Bland, Statistics notes. Units of analysis, BMJ 314 (1997) 1874.

[42] M. Porta, A Dictionary of Epidemiology, fifth ed., New York Oxford University Press,

New York and Oxford, 2008.

[43] V. Gallo, et al., STrengthening the reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology-

Molecular Epidemiology (STROBE-ME): an extension of the STROBE statement, Eur.

J. Clin. Investig. 42 (1) (2012) 1–16.

[44] D.F. Garway-Heath, et al., Latanoprost for open-angle glaucoma (UKGTS): a ran-

domised, multicentre, placebo-controlled trial, Lancet 385 (9975) (2015) 1295–1304.

[45] K. Strimbu, J.A. Tavel, What are biomarkers? Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 5 (6) (2010)

463–466.

[46] B. Efron, T. Hastie, Computer Age Statistical Inference: Algorithms, Evidence, and Data

Science, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2016.

[47] I.J. MacCormick, et al., Accurate, fast, data efficient and interpretable glaucoma diag-

nosis with automated spatial analysis of the whole cup to disc profile, PLoS ONE 14 (1)

(2019) e0209409.