Page 138 - Designing Sociable Robots

P. 138

breazeal-79017 book March 18, 2002 14:5

The Motivation System 119

Drives over- Emotion

Elicitors

whelming Sorrow Disgust

V, S

V,S

high arousal,

Releasers Anger

Affective negative Surprise

Assessment valence, A, S Boredom A,V

Big S

closed stance Calm

Threat S

Close Threat

SM

Fear Joy Interest

Fast A,V,S A A,S

Motion

success,

frustration

Emotion

Arbitration

Behavior Sorrow Boredom

System Interest Calm

Flee Fear

Behavior

Surprise Joy Disgust Anger

Motor net arousal, valence, stance

Systems

Escape

Motor Express Express Express

Skill Voice Face Posture

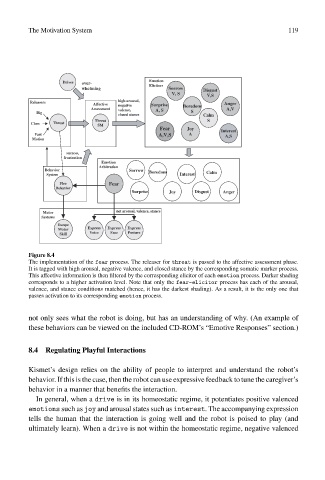

Figure 8.4

The implementation of the fear process. The releaser for threat is passed to the affective assessment phase.

It is tagged with high arousal, negative valence, and closed stance by the corresponding somatic marker process.

This affective information is then filtered by the corresponding elicitor of each emotion process. Darker shading

corresponds to a higher activation level. Note that only the fear-elicitor process has each of the arousal,

valence, and stance conditions matched (hence, it has the darkest shading). As a result, it is the only one that

passes activation to its corresponding emotion process.

not only sees what the robot is doing, but has an understanding of why. (An example of

these behaviors can be viewed on the included CD-ROM’s “Emotive Responses” section.)

8.4 Regulating Playful Interactions

Kismet’s design relies on the ability of people to interpret and understand the robot’s

behavior. If this is the case, then the robot can use expressive feedback to tune the caregiver’s

behavior in a manner that benefits the interaction.

In general, when a drive is in its homeostatic regime, it potentiates positive valenced

emotions such as joy and arousal states such as interest. The accompanying expression

tells the human that the interaction is going well and the robot is poised to play (and

ultimately learn). When a drive is not within the homeostatic regime, negative valenced