Page 222 - Earth's Climate Past and Future

P. 222

198 PART III • Orbital-Scale Climate Change

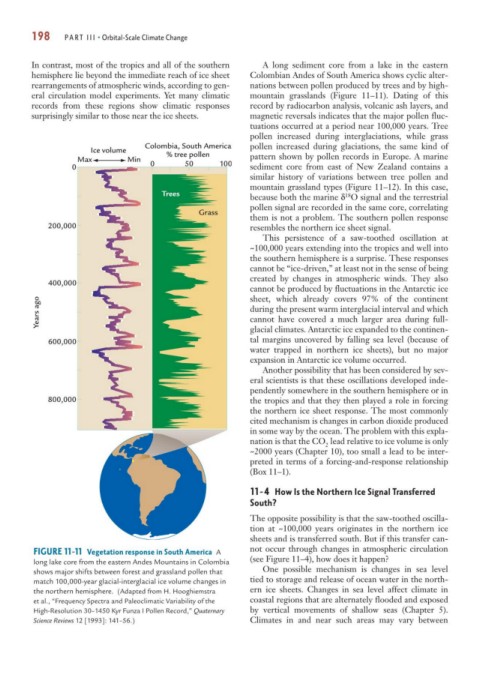

In contrast, most of the tropics and all of the southern A long sediment core from a lake in the eastern

hemisphere lie beyond the immediate reach of ice sheet Colombian Andes of South America shows cyclic alter-

rearrangements of atmospheric winds, according to gen- nations between pollen produced by trees and by high-

eral circulation model experiments. Yet many climatic mountain grasslands (Figure 11–11). Dating of this

records from these regions show climatic responses record by radiocarbon analysis, volcanic ash layers, and

surprisingly similar to those near the ice sheets. magnetic reversals indicates that the major pollen fluc-

tuations occurred at a period near 100,000 years. Tree

pollen increased during interglaciations, while grass

Colombia, South America pollen increased during glaciations, the same kind of

Ice volume % tree pollen

Max Min pattern shown by pollen records in Europe. A marine

0 0 50 100 sediment core from east of New Zealand contains a

similar history of variations between tree pollen and

mountain grassland types (Figure 11–12). In this case,

Trees because both the marine δ O signal and the terrestrial

18

pollen signal are recorded in the same core, correlating

Grass

them is not a problem. The southern pollen response

200,000 resembles the northern ice sheet signal.

This persistence of a saw-toothed oscillation at

~100,000 years extending into the tropics and well into

the southern hemisphere is a surprise. These responses

cannot be “ice-driven,” at least not in the sense of being

created by changes in atmospheric winds. They also

400,000

cannot be produced by fluctuations in the Antarctic ice

sheet, which already covers 97% of the continent

Years ago during the present warm interglacial interval and which

cannot have covered a much larger area during full-

glacial climates. Antarctic ice expanded to the continen-

600,000 tal margins uncovered by falling sea level (because of

water trapped in northern ice sheets), but no major

expansion in Antarctic ice volume occurred.

Another possibility that has been considered by sev-

eral scientists is that these oscillations developed inde-

pendently somewhere in the southern hemisphere or in

800,000 the tropics and that they then played a role in forcing

the northern ice sheet response. The most commonly

cited mechanism is changes in carbon dioxide produced

in some way by the ocean. The problem with this expla-

nation is that the CO lead relative to ice volume is only

2

~2000 years (Chapter 10), too small a lead to be inter-

preted in terms of a forcing-and-response relationship

(Box 11–1).

11-4 How Is the Northern Ice Signal Transferred

South?

The opposite possibility is that the saw-toothed oscilla-

tion at ~100,000 years originates in the northern ice

sheets and is transferred south. But if this transfer can-

not occur through changes in atmospheric circulation

FIGURE 11-11 Vegetation response in South America A

long lake core from the eastern Andes Mountains in Colombia (see Figure 11–4), how does it happen?

shows major shifts between forest and grassland pollen that One possible mechanism is changes in sea level

match 100,000-year glacial-interglacial ice volume changes in tied to storage and release of ocean water in the north-

the northern hemisphere. (Adapted from H. Hooghiemstra ern ice sheets. Changes in sea level affect climate in

et al., “Frequency Spectra and Paleoclimatic Variability of the coastal regions that are alternately flooded and exposed

High-Resolution 30–1450 Kyr Funza I Pollen Record,” Quaternary by vertical movements of shallow seas (Chapter 5).

Science Reviews 12 [1993]: 141–56.) Climates in and near such areas may vary between