Page 61 - Earth's Climate Past and Future

P. 61

CHAPTER 2 • Climate Archives, Data, and Models 37

When subdivision of the fine material is physically

Source impossible, chemical analysis offers an alternative, if

reservoir each source of fine sediment is marked with a distinctive

2

chemical value. One typical chemical marker is the ratio

of isotopes of a single element. These different inputs

Source Flux 2 Source combine to determine the average value of the fine-

reservoir reservoir grained sediment (see Figure 2–23). The goal of this

1 3 kind of analysis is to understand how the individual

fluxes combine to create this average value.

Flux 1 Flux 3 Chemical Reservoirs A different modeling approach

is used for geochemical tracers that are transported in dis-

solved form. Mass balance models divide Earth’s systems

into reservoirs, including the atmosphere, ocean, ice,

vegetation, and sediments. The ocean is the most impor-

tant reservoir: it receives almost all erosional products

from the continents, it interacts with all of the other reser-

voirs, and it deposits tracers in well-preserved sedimentary

Receiving reservoir with average archives.

tagged value of three inputs

The ocean reservoir is somewhat analogous to a

bathtub (Figure 2–24). It gradually receives the inputs

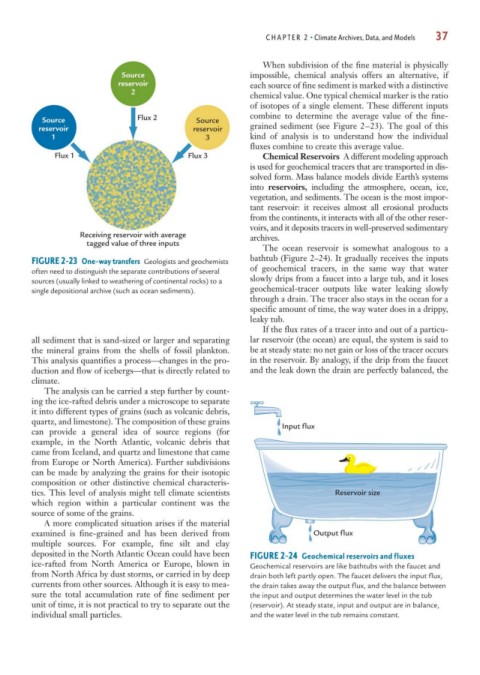

FIGURE 2-23 One-way transfers Geologists and geochemists

often need to distinguish the separate contributions of several of geochemical tracers, in the same way that water

sources (usually linked to weathering of continental rocks) to a slowly drips from a faucet into a large tub, and it loses

single depositional archive (such as ocean sediments). geochemical-tracer outputs like water leaking slowly

through a drain. The tracer also stays in the ocean for a

specific amount of time, the way water does in a drippy,

leaky tub.

If the flux rates of a tracer into and out of a particu-

all sediment that is sand-sized or larger and separating lar reservoir (the ocean) are equal, the system is said to

the mineral grains from the shells of fossil plankton. be at steady state: no net gain or loss of the tracer occurs

This analysis quantifies a process—changes in the pro- in the reservoir. By analogy, if the drip from the faucet

duction and flow of icebergs—that is directly related to and the leak down the drain are perfectly balanced, the

climate.

The analysis can be carried a step further by count-

ing the ice-rafted debris under a microscope to separate

it into different types of grains (such as volcanic debris,

quartz, and limestone). The composition of these grains Input flux

can provide a general idea of source regions (for

example, in the North Atlantic, volcanic debris that

came from Iceland, and quartz and limestone that came

from Europe or North America). Further subdivisions

can be made by analyzing the grains for their isotopic

composition or other distinctive chemical characteris-

tics. This level of analysis might tell climate scientists Reservoir size

which region within a particular continent was the

source of some of the grains.

A more complicated situation arises if the material

examined is fine-grained and has been derived from Output flux

multiple sources. For example, fine silt and clay

deposited in the North Atlantic Ocean could have been FIGURE 2-24 Geochemical reservoirs and fluxes

ice-rafted from North America or Europe, blown in Geochemical reservoirs are like bathtubs with the faucet and

from North Africa by dust storms, or carried in by deep drain both left partly open. The faucet delivers the input flux,

currents from other sources. Although it is easy to mea- the drain takes away the output flux, and the balance between

sure the total accumulation rate of fine sediment per the input and output determines the water level in the tub

unit of time, it is not practical to try to separate out the (reservoir). At steady state, input and output are in balance,

individual small particles. and the water level in the tub remains constant.