Page 23 - Hydrogeology Principles and Practice

P. 23

HYDC01 12/5/05 5:44 PM Page 6

BO X

The aqueducts of Rome

1. 1

The remarkable organization and engineering skills of the Roman civil- hydrogeological map (Boni et al. 1986) as issuing from permeable vol-

3 −1

ization are demonstrated in the book written by Sextus Julius Frontinus canic rocks with a mean discharge of 1.0 m s (Fig. 1). Frontinus also

and translated into English by C.E. Bennett (1969). In the year 97 ad, describes the Marcia aqueduct with its intake issuing from a tranquil

Frontinus was appointed to the post of water commissioner, during the pool of deep green hue. The length of the water-carrying conduit is

1

tenure of which he wrote the De Aquis. The work is of a technical nature, 61,710 /2 paces (91.5 km), with 10.3 km on arches. Today, the source

written partly for his own instruction, and partly for the benefit of others. of the Marcia spring is known to issue from extensively fractured lime-

3 −1

In it, Frontinus painstakingly details every aspect of the construction and stone rocks with a copious mean discharge of 5.4 m s .

maintenance of the aqueducts existing in his day. After enumerating the lengths and courses of the several aqueducts,

For more than four hundred years, the city of Rome was supplied with Frontinus enthuses: ‘with such an array of indispensable structures carry-

water drawn from the River Tiber, and from wells and springs. Springs ing so many waters, compare, if you will, the idle Pyramids or the useless,

were held in high esteem, and treated with veneration. Many were though famous, works of the Greeks!’ To protect the aqueducts from wil-

believed to have healing properties, such as the springs of Juturna, part ful pollution, a law was introduced such that: ‘No one shall with malice

of a fountain known from the south side of the Roman Forum. As shown pollute the waters where they issue publicly. Should any one pollute

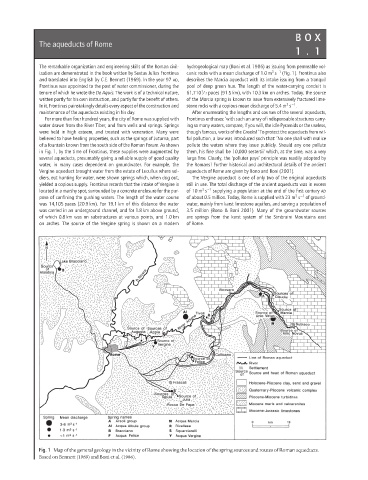

in Fig. 1, by the time of Frontinus, these supplies were augmented by them, his fine shall be 10,000 sestertii’ which, at the time, was a very

several aqueducts, presumably giving a reliable supply of good quality large fine. Clearly, the ‘polluter pays’ principle was readily adopted by

water, in many cases dependent on groundwater. For example, the the Romans! Further historical and architectural details of the ancient

Vergine aqueduct brought water from the estate of Lucullus where sol- aqueducts of Rome are given by Bono and Boni (2001).

diers, out hunting for water, were shown springs which, when dug out, The Vergine aqueduct is one of only two of the original aqueducts

yielded a copious supply. Frontinus records that the intake of Vergine is still in use. The total discharge of the ancient aqueducts was in excess

3 −1

located in a marshy spot, surrounded by a concrete enclosure for the pur- of 10 m s supplying a population at the end of the first century ad

3 −1

pose of confining the gushing waters. The length of the water course of about 0.5 million. Today, Rome is supplied with 23 m s of ground-

was 14,105 paces (20.9 km). For 19.1 km of this distance the water water, mainly from karst limestone aquifers, and serving a population of

was carried in an underground channel, and for 1.8 km above ground, 3.5 million (Bono & Boni 2001). Many of the groundwater sources

of which 0.8 km was on substructures at various points, and 1.0 km are springs from the karst system of the Simbruini Mountains east

on arches. The source of the Vergine spring is shown on a modern of Rome.

Fig. 1 Map of the general geology in the vicinity of Rome showing the location of the spring sources and routes of Roman aqueducts.

Based on Bennett (1969) and Boni et al. (1986).