Page 207 - Introduction to Autonomous Mobile Robots

P. 207

192

B Chapter 5

A

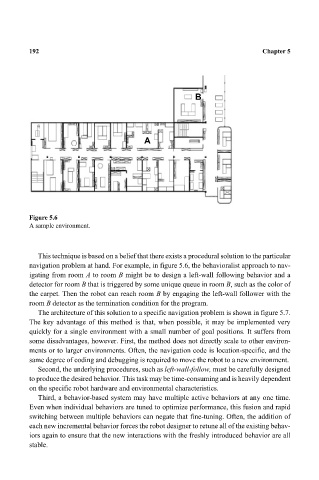

Figure 5.6

A sample environment.

This technique is based on a belief that there exists a procedural solution to the particular

navigation problem at hand. For example, in figure 5.6, the behavioralist approach to nav-

igating from room A to room B might be to design a left-wall following behavior and a

detector for room B that is triggered by some unique queue in room B, such as the color of

the carpet. Then the robot can reach room B by engaging the left-wall follower with the

room B detector as the termination condition for the program.

The architecture of this solution to a specific navigation problem is shown in figure 5.7.

The key advantage of this method is that, when possible, it may be implemented very

quickly for a single environment with a small number of goal positions. It suffers from

some disadvantages, however. First, the method does not directly scale to other environ-

ments or to larger environments. Often, the navigation code is location-specific, and the

same degree of coding and debugging is required to move the robot to a new environment.

Second, the underlying procedures, such as left-wall-follow, must be carefully designed

to produce the desired behavior. This task may be time-consuming and is heavily dependent

on the specific robot hardware and environmental characteristics.

Third, a behavior-based system may have multiple active behaviors at any one time.

Even when individual behaviors are tuned to optimize performance, this fusion and rapid

switching between multiple behaviors can negate that fine-tuning. Often, the addition of

each new incremental behavior forces the robot designer to retune all of the existing behav-

iors again to ensure that the new interactions with the freshly introduced behavior are all

stable.