Page 262 - Microtectonics

P. 262

254 9 · Natural Microgauges

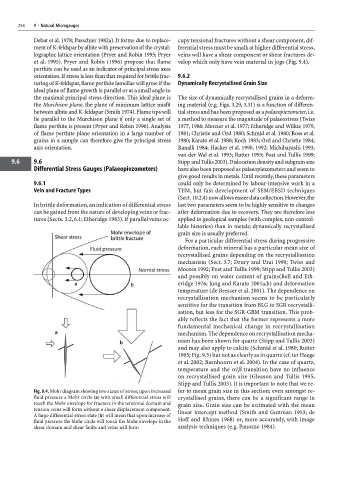

Debat et al. 1978; Passchier 1982a). It forms due to replace- cupy tensional fractures without a shear component, dif-

ment of K-feldspar by albite with preservation of the crystal- ferential stress must be small; at higher differential stress,

lographic lattice orientation (Pryer and Robin 1995; Pryer veins will have a shear component or shear fractures de-

et al. 1995). Pryer and Robin (1996) propose that flame velop which only have vein material in jogs (Fig. 9.4).

perthite can be used as an indicator of principal stress axes

orientation. If stress is less than that required for brittle frac- 9.6.2

turing of K-feldspar, flame perthite lamellae will grow if the Dynamically Recrystallised Grain Size

ideal plane of flame growth is parallel or at a small angle to

the maximal principal stress direction. This ideal plane is The size of dynamically recrystallised grains in a deform-

the Murchison plane, the plane of minimum lattice misfit ing material (e.g. Figs. 3.29, 3.31) is a function of differen-

between albite and K-feldspar (Smith 1974). Flame tips will tial stress and has been proposed as a palaeopiezometer, i.e.

lie parallel to the Murchison plane if only a single set of a method to measure the magnitude of palaeostress (Twiss

flame perthite is present (Pryer and Robin 1996). Analysis 1977, 1986; Mercier et al. 1977; Etheridge and Wilkie 1979,

of flame perthite plane orientation in a large number of 1981; Christie and Ord 1980; Schmid et al. 1980; Ross et al.

grains in a sample can therefore give the principal stress 1980; Karato et al. 1980; Koch 1983; Ord and Christie 1984;

axis orientation. Ranalli 1984; Hacker et al. 1990, 1992; Michibayashi 1993;

van der Wal et al. 1993; Rutter 1995; Post and Tullis 1999;

9.6 9.6 Stipp and Tullis 2003). Dislocation density and subgrain size

Differential Stress Gauges (Palaeopiezometers) have also been proposed as palaeopiezometers and seem to

give good results in metals. Until recently, these parameters

9.6.1 could only be determined by labour-intensive work in a

Vein and Fracture Types TEM, but fast development of SEM/EBSD techniques

(Sect. 10.2.4) now allows easier data collection. However, the

In brittle deformation, an indication of differential stress last two parameters seem to be highly sensitive to changes

can be gained from the nature of developing veins or frac- after deformation due to recovery. They are therefore less

tures (Sects. 3.2, 6.1; Etheridge 1983). If parallel veins oc- applied in geological samples (with complex, non-control-

lable histories) than in metals; dynamically recrystallised

grain size is usually preferred.

For a particular differential stress during progressive

deformation, each mineral has a particular mean size of

recrystallised grains depending on the recrystallisation

mechanism (Sect. 3.7; Drury and Urai 1990; Twiss and

Moores 1992; Post and Tullis 1999; Stipp and Tullis 2003)

and possibly on water content of grains(Bell and Eth-

eridge 1976; Jung and Karato 2001a,b) and deformation

temperature (de Bresser et al. 2001). The dependence on

recrystallisation mechanism seems to be particularly

sensitive for the transition from BLG to SGR recrystalli-

sation, but less for the SGR-GBM transition. This prob-

ably reflects the fact that the former represents a more

fundamental mechanical change in recrystallisation

mechanism. The dependence on recrystallisation mecha-

nism has been shown for quartz (Stipp and Tullis 2003)

and may also apply to calcite (Schmid et al. 1980; Rutter

1995; Fig. 9.5) but not as clearly as in quartz (cf. ter Heege

et al. 2002; Barnhoorn et al. 2004). In the case of quartz,

temperature and the α/β transition have no influence

on recrystallised grain size (Gleason and Tullis 1995;

Stipp and Tullis 2003). It is important to note that we re-

Fig. 9.4. Mohr diagram showing two states of stress; upon increased fer to mean grain size in this section; even amongst re-

fluid pressure a Mohr circle (a) with small differential stress will crystallised grains, there can be a significant range in

touch the Mohr envelope for fracture in the tensional domain and grain size. Grain size can be estimated with the mean

tension veins will form without a shear displacement component.

A large differential stress state (b) will mean that upon increase of linear intercept method (Smith and Guttman 1953; de

fluid pressure the Mohr circle will touch the Mohr envelope in the Hoff and Rhines 1968) or, more accurately, with image

shear domain and shear faults and veins will form analysis techniques (e.g. Panozzo 1984).