Page 145 - Partition & Adsorption of Organic Contaminants in Environmental Systems

P. 145

136 CONTAMINANT SORPTION TO SOILS AND NATURAL SOLIDS

composition in Figure 7.12, an assumed carbon content of about 54% in SOM

would seem more appropriate. This would change the conversion between K om

and K oc to K oc 1.85K om.)

Since the magnitude of K oc (or K om) reflects the difference in solute solu-

bilities in SOM and water, which varies with the solute, the slopes and inter-

cepts in Eqs. (7.13) and (7.14) would vary with the compounds studied.

For a single correlation to suffice for different classes of solutes, the solutes

with the same S w or K ow value must exhibit nearly the same (supercooled-

liquid) solubility in SOM [i.e., about the same S om value in Eq. (7.10)].

Although the data for many low-polarity solutes, or for a class of solutes

with similar molecular groups, may largely satisfy this requirement, it is not

observed by all solutes. In such correlations, the slope reflects the (differen-

tial) change in logS om with the change in the solute’s logS w or logK ow value,

while the intercept is the theoretical logK oc (or logK om) value of a hypothet-

ical reference solute having logS w = 0 or logK ow = 0. As the S om value changes

with solute polarity in a different manner for different series of solutes, the

slope and intercept of the correlation change accordingly. For example, Briggs

(1981) measured the logK om values of a wide variety of polar compounds and

pesticides (anilines, anilides, phenols, nitrobenzenes, substituted ureas, carba-

mates, organophosphates, and others) on soil and found the correlation

between logK om and logK ow as

logK om = 0.52logK ow + 0.64 (7.15)

2

with n = 105 and r = 0.90. Most compounds in Briggs’s study have logK ow

< 3, however. As seen, Eq. (7.15) gives a much smaller slope but a much larger

intercept than does Eq. (7.14). At logK ow < 3, as for most polar solutes, the

logK om values estimated by Eq. (7.15) are comparable in magnitude with the

respective logK ow values and thus considerably higher than the logK om values

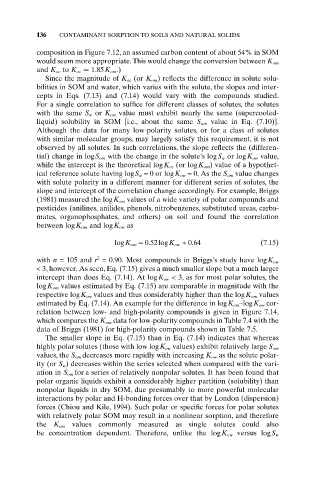

estimated by Eq. (7.14). An example for the difference in logK om–logK ow cor-

relation between low- and high-polarity compounds is given in Figure 7.14,

which compares the K om data for low-polarity compounds in Table 7.4 with the

data of Briggs (1981) for high-polarity compounds shown in Table 7.5.

The smaller slope in Eq. (7.15) than in Eq. (7.14) indicates that whereas

highly polar solutes (those with low logK ow values) exhibit relatively large S om

values, the S om decreases more rapidly with increasing K ow as the solute polar-

ity (or S w ) decreases within the series selected when compared with the vari-

ation in S om for a series of relatively nonpolar solutes. It has been found that

polar organic liquids exhibit a considerably higher partition (solubility) than

nonpolar liquids in dry SOM, due presumably to more powerful molecular

interactions by polar and H-bonding forces over that by London (dispersion)

forces (Chiou and Kile, 1994). Such polar or specific forces for polar solutes

with relatively polar SOM may result in a nonlinear sorption, and therefore

the K om values commonly measured as single solutes could also

be concentration dependent. Therefore, unlike the logK ow versus logS w