Page 162 - Foundations of Cognitive Psychology : Core Readings

P. 162

166 Philip G. Zimbardo and Richard J. Gerrig

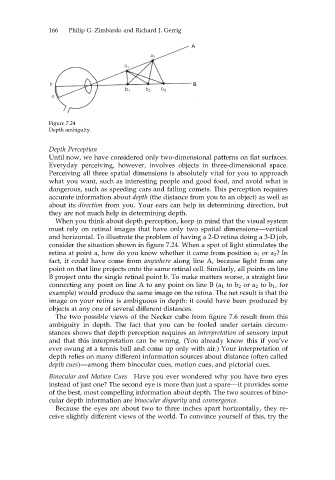

Figure 7.24

Depth ambiguity.

Depth Perception

Until now, we have considered only two-dimensional patterns on flat surfaces.

Everyday perceiving, however, involves objects in three-dimensional space.

Perceiving all three spatial dimensions is absolutely vital for you to approach

what you want, such as interesting people and good food, and avoid what is

dangerous, such as speeding cars and falling comets. This perception requires

accurate information about depth (the distance from you to an object) as well as

about its direction from you. Your ears can help in determining direction, but

they are not much help in determining depth.

When you think about depth perception, keep in mind that the visual system

must rely on retinal images that have only two spatial dimensions—vertical

and horizontal. To illustrate the problem of having a 2-D retina doing a 3-D job,

consider the situation shown in figure 7.24. When a spot of light stimulates the

retina at point a, how do you know whether it came from position a 1 or a 2 ?In

fact, it could have come from anywhere along line A, because light from any

point on that line projects onto the same retinal cell. Similarly, all points on line

B project onto the single retinal point b. To make matters worse, a straight line

connecting any point on line A to any point on line B (a 1 to b 2 or a 2 to b 1 ,for

example) wouldproduce thesameimage on theretina. Thenet result is that the

image on your retina is ambiguous in depth: it could have been produced by

objects at any one of several different distances.

Thetwo possibleviews of theNeckercubefromfigure 7.6resultfromthis

ambiguity in depth. The fact that you can be fooled under certain circum-

stances shows that depth perception requires an interpretation of sensory input

and that this interpretation can be wrong. (You already know this if you’ve

ever swung at a tennis ball and come up only with air.) Your interpretation of

depth relies on many different information sources about distance (often called

depth cues)—among them binocular cues, motion cues, and pictorial cues.

Binocular and Motion Cues Have you ever wondered why you have two eyes

instead of just one? The second eye is more than just a spare—it provides some

of the best, most compelling information about depth. The two sources of bino-

cular depth information are binocular disparity and convergence.

Because the eyes are about two to three inches apart horizontally, they re-

ceive slightly different views of the world. To convince yourself of this, try the