Page 323 - T. Anderson-Fracture Mechanics - Fundamentals and Applns.-CRC (2005)

P. 323

1656_C007.fm Page 303 Monday, May 23, 2005 5:54 PM

Fracture Toughness Testing of Metals 303

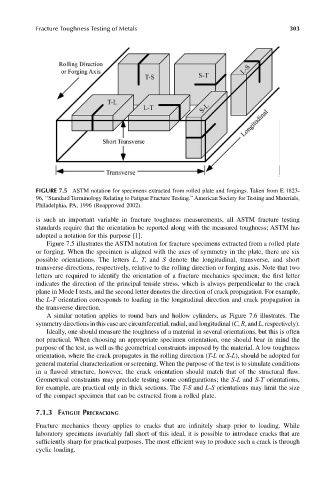

FIGURE 7.5 ASTM notation for specimens extracted from rolled plate and forgings. Taken from E 1823-

96, ‘‘Standard Terminology Relating to Fatigue Fracture Testing.’’ American Society for Testing and Materials,

Philadelphia, PA, 1996 (Reapproved 2002).

is such an important variable in fracture toughness measurements, all ASTM fracture testing

standards require that the orientation be reported along with the measured toughness; ASTM has

adopted a notation for this purpose [1].

Figure 7.5 illustrates the ASTM notation for fracture specimens extracted from a rolled plate

or forging. When the specimen is aligned with the axes of symmetry in the plate, there are six

possible orientations. The letters L, T, and S denote the longitudinal, transverse, and short

transverse directions, respectively, relative to the rolling direction or forging axis. Note that two

letters are required to identify the orientation of a fracture mechanics specimen; the first letter

indicates the direction of the principal tensile stress, which is always perpendicular to the crack

plane in Mode I tests, and the second letter denotes the direction of crack propagation. For example,

the L-T orientation corresponds to loading in the longitudinal direction and crack propagation in

the transverse direction.

A similar notation applies to round bars and hollow cylinders, as Figure 7.6 illustrates. The

symmetry directions in this case are circumferential, radial, and longitudinal (C, R, and L, respectively).

Ideally, one should measure the toughness of a material in several orientations, but this is often

not practical. When choosing an appropriate specimen orientation, one should bear in mind the

purpose of the test, as well as the geometrical constraints imposed by the material. A low toughness

orientation, where the crack propagates in the rolling direction (T-L or S-L), should be adopted for

general material characterization or screening. When the purpose of the test is to simulate conditions

in a flawed structure, however, the crack orientation should match that of the structural flaw.

Geometrical constraints may preclude testing some configurations; the S-L and S-T orientations,

for example, are practical only in thick sections. The T-S and L-S orientations may limit the size

of the compact specimen that can be extracted from a rolled plate.

7.1.3 FATIGUE PRECRACKING

Fracture mechanics theory applies to cracks that are infinitely sharp prior to loading. While

laboratory specimens invariably fall short of this ideal, it is possible to introduce cracks that are

sufficiently sharp for practical purposes. The most efficient way to produce such a crack is through

cyclic loading.