Page 79 -

P. 79

Chapter

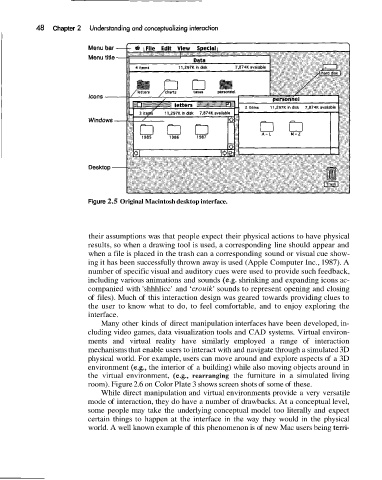

Figure 2.5 Original Macintosh desktop interface.

their assumptions was that people expect their physical actions to have physical

results, so when a drawing tool is used, a corresponding line should appear and

when a file is placed in the trash can a corresponding sound or visual cue show-

ing it has been successfully thrown away is used (Apple Computer Inc., 1987). A

number of specific visual and auditory cues were used to provide such feedback,

including various animations and sounds (e.g. shrinking and expanding icons ac-

companied with 'shhhlicc' and 'crouik' sounds to represent opening and closing

of files). Much of this interaction design was geared towards providing clues to

the user to know what to do, to feel comfortable, and to enjoy exploring the

interface.

Many other kinds of direct manipulation interfaces have been developed, in-

cluding video games, data visualization tools and CAD systems. Virtual environ-

ments and virtual reality have similarly employed a range of interaction

mechanisms that enable users to interact with and navigate through a simulated 3D

physical world. For example, users can move around and explore aspects of a 3D

environment (e.g., the interior of a building) while also moving objects around in

the virtual environment, (e.g., rearranging the furniture in a simulated living

room). Figure 2.6 on Color Plate 3 shows screen shots of some of these.

While direct manipulation and virtual environments provide a very versatile

mode of interaction, they do have a number of drawbacks. At a conceptual level,

some people may take the underlying conceptual model too literally and expect

certain things to happen at the interface in the way they would in the physical

world. A well known example of this phenomenon is of new Mac users being terri-