Page 586 - 04. Subyek Engineering Materials - Manufacturing, Engineering and Technology SI 6th Edition - Serope Kalpakjian, Stephen Schmid (2009)

P. 586

»

Top view Section 21.2 Mechamcs of Cutting

a

Z

f

Tool

2 "I o -|-00| Cmp

ooo ip

f

Workpiece

X workpiece Chip

(H) (D) (C)

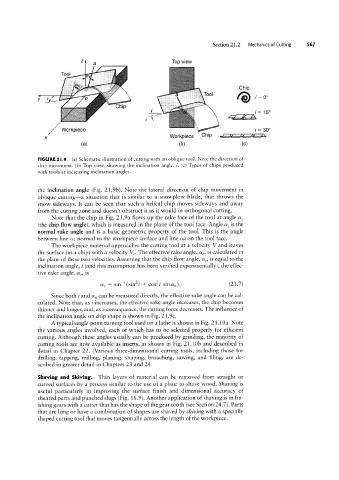

FIGURE 2l.9 (a) Schematic illustration of cutting with an oblique tool. Note the direction of

chip movement. (b) Top view, showing the inclination angle, i. (c) Types of chips produced

with tools at increasing inclination angles.

the inclination angle (Fig. 21.9b). Note the lateral direction of chip movement in

oblique cutting-a situation that is similar to a snowplow blade, that throws the

snow sideways. It can be seen that such a helical chip moves sideways and away

from the cutting zone and doesn’t obstruct it as it would in orthogonal cutting.

Note that the chip in Fig. 21.9a flows up the rake face of the tool at angle ag

(the chip flow angle), which is measured in the plane of the tool face. Angle oz, is the

normal rake angle and is a basic geometric property of the tool. This is the angle

between line oz normal to the workpiece surface and line oa on the tool face.

The workpiece material approaches the cutting tool at a velocity V and leaves

the surface (as a chip) with a velocity VC. The effective rake angle, ae, is calculated in

the plane of these two velocities. Assuming that the chip flow angle, af, is equal to the

inclination angle, i (and this assumption has been verified experimentally), the effec-

tive rake angle, ae, is

ae = sinT1(sin2i + coszi sinan). (21.7)

Since both i and an can be measured directly, the effective rake angle can be cal-

culated. Note that, as i increases, the effective rake angle increases, the chip becomes

thinner and longer, and, as a consequence, the cutting force decreases. The influence of

the inclination angle on chip shape is shown in Fig. 21.9c.

A typical single-point turning tool used on a lathe is shown in Fig. 21.10a. Note

the various angles involved, each of which has to be selected properly for efficient

cutting. Although these angles usually can be produced by grinding, the majority of

cutting tools are now available as inserts, as shown in Fig. 21.1()b and described in

detail in Chapter 22. (Various three-dimensional cutting tools, including those for

drilling, tapping, milling, planing, shaping, broaching, sawing, and filing, are de-

scribed in greater detail in Chapters 23 and 24.

Shaving and Skiving. Thin layers of material can be removed from straight or

curved surfaces by a process similar to the use of a plane to shave wood. Shaving is

useful particularly in improving the surface finish and dimensional accuracy of

sheared parts and punched slugs (Fig. 16.9). Another application of shaving is in fin-

ishing gears with a cutter that has the shape of the gear tooth (see Section 24.7). Parts

that are long or have a combination of shapes are shaved by skit/ing with a specially

shaped cutting tool that moves tangentially across the length of the workpiece.