Page 225 - Microtectonics

P. 225

7.6 · Problematic Porphyroblast Microstructures 215

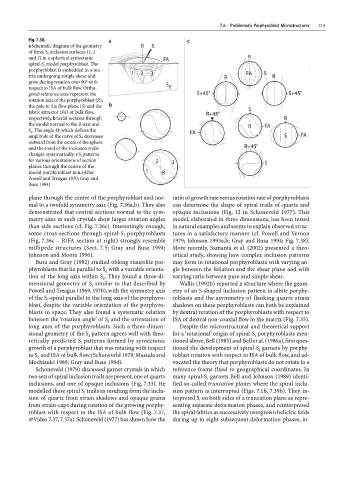

Fig. 7.36.

a Schematic diagram of the geometry

of three S inclusion surfaces (1, 2

i

and 3) in a spherical syntectonic

spiral-S i model porphyroblast. The

porphyroblast is embedded in a ma-

trix undergoing simple shear and

grew during rotation over 90° with

respect to ISA of bulk flow. Ortho-

gonal reference axes represent the

rotation axis of the porphyroblast (R),

the pole to the flow plane (S) and the

fabric attractor (FA) of bulk flow,

respectively. b Serial sections through

the model normal to the R-axis and

S e . The angle Θ, which defines the

amplitude of the curve of S , decreases

i

outward from the centre of the sphere

and the trend of the inclusion trails

changes systematically. c S patterns

i

for various orientations of section

planes through the centre of the

model porphyroblast in a. (After

Powell and Treagus 1970; Gray and

Busa 1994)

plane through the centre of the porphyroblast and nor- ratio of growth rate versus rotation rate of porphyroblasts

mal to a twofold symmetry axis (Fig. 7.36a,b). They also can determine the shape of spiral trails of quartz and

demonstrated that central sections normal to the sym- opaque inclusions (Fig. 12 in Schoneveld 1977). This

metry axes in such crystals show larger rotation angles model, elaborated in three dimensions, has been tested

than side sections (cf. Fig. 7.36c). Interestingly enough, in natural examples and seems to explain observed struc-

some cross-sections through spiral-S porphyroblasts tures in a satisfactory manner (cf. Powell and Vernon

i

(Fig. 7.36c – R/FA section at right) strongly resemble 1979; Johnson 1993a,b; Gray and Busa 1994; Fig. 7.38).

millipede structures (Sect. 7.5; Gray and Busa 1994; More recently, Samanta et al. (2002) presented a theo-

Johnson and Moore 1996). retical study, showing how complex inclusion patterns

Busa and Gray (1992) studied oblong staurolite por- may form in rotational porphyroblasts with varying an-

phyroblasts that lie parallel to S with a variable orienta- gle between the foliation and the shear plane and with

e

tion of the long axis within S . They found a three-di- varying ratio between pure and simple shear.

e

mensional geometry of S similar to that described by Wallis (1992b) reported a structure where the geom-

i

Powell and Treagus (1969, 1970), with the symmetry axis etry of an S-shaped inclusion pattern in albite porphy-

of the S -spiral parallel to the long axis of the porphyro- roblasts and the asymmetry of flanking quartz strain

i

blast, despite the variable orientation of the porphyro- shadows on these porphyroblasts can both be explained

blasts in space. They also found a systematic relation by dextral rotation of the porphyroblasts with respect to

between the ‘rotation angle’ of S and the orientation of ISA of dextral non-coaxial flow in the matrix (Fig. 7.35).

i

long axes of the porphyroblasts. Such a three-dimen- Despite the microstructural and theoretical support

sional geometry of the S pattern agrees well with theo- for a ‘rotational’ origin of spiral-S porphyroblasts men-

i

i

retically predicted S patterns formed by syntectonic tioned above, Bell (1985) and Bell et al. (1986a), first ques-

i

growth of a porphyroblast that was rotating with respect tioned the development of spiral-S garnets by porphy-

i

to S and ISA of bulk flow (Schoneveld 1979; Masuda and roblast rotation with respect to ISA of bulk flow, and ad-

e

Mochizuki 1989; Gray and Busa 1994). vocated the theory that porphyroblasts do not rotate in a

Schoneveld (1979) discussed garnet crystals in which reference frame fixed to geographical coordinates. In

two sets of spiral inclusion trails are present, one of quartz many spiral-S garnets Bell and Johnson (1989) identi-

i

inclusions, and one of opaque inclusions (Fig. 7.33). He fied so-called truncation planes where the spiral inclu-

modelled these spiral S trails as resulting from the inclu- sion pattern is interrupted (Figs. 7.1b, 7.39b). They in-

i

sion of quartz from strain shadows and opaque grains terpreted S on both sides of a truncation plane as repre-

i

from strain-caps during rotation of the growing porphy- senting separate deformation phases, and reinterpreted

roblast with respect to the ISA of bulk flow (Fig. 7.37, the spiral fabrics as successively overgrown helicitic folds

×Video 7.37, 7.37a). Schoneveld (1977) has shown how the during up to eight subsequent deformation phases, in-