Page 524 - Shigley's Mechanical Engineering Design

P. 524

bud29281_ch09_475-516.qxd 12/16/2009 7:13 pm Page 498 pinnacle 203:MHDQ196:bud29281:0073529281:bud29281_pagefiles:

498 Mechanical Engineering Design

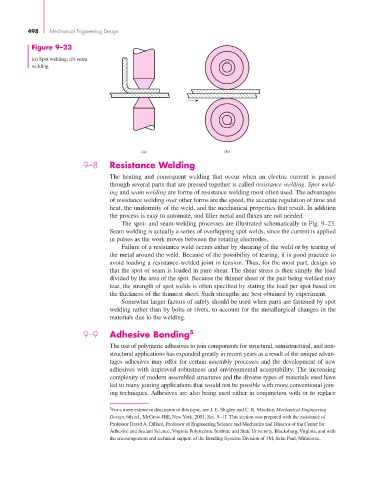

Figure 9–23

(a) Spot welding; (b) seam

welding.

(a) (b)

9–8 Resistance Welding

The heating and consequent welding that occur when an electric current is passed

through several parts that are pressed together is called resistance welding. Spot weld-

ing and seam welding are forms of resistance welding most often used. The advantages

of resistance welding over other forms are the speed, the accurate regulation of time and

heat, the uniformity of the weld, and the mechanical properties that result. In addition

the process is easy to automate, and filler metal and fluxes are not needed.

The spot- and seam-welding processes are illustrated schematically in Fig. 9–23.

Seam welding is actually a series of overlapping spot welds, since the current is applied

in pulses as the work moves between the rotating electrodes.

Failure of a resistance weld occurs either by shearing of the weld or by tearing of

the metal around the weld. Because of the possibility of tearing, it is good practice to

avoid loading a resistance-welded joint in tension. Thus, for the most part, design so

that the spot or seam is loaded in pure shear. The shear stress is then simply the load

divided by the area of the spot. Because the thinner sheet of the pair being welded may

tear, the strength of spot welds is often specified by stating the load per spot based on

the thickness of the thinnest sheet. Such strengths are best obtained by experiment.

Somewhat larger factors of safety should be used when parts are fastened by spot

welding rather than by bolts or rivets, to account for the metallurgical changes in the

materials due to the welding.

9–9 Adhesive Bonding 5

The use of polymeric adhesives to join components for structural, semistructural, and non-

structural applications has expanded greatly in recent years as a result of the unique advan-

tages adhesives may offer for certain assembly processes and the development of new

adhesives with improved robustness and environmental acceptability. The increasing

complexity of modern assembled structures and the diverse types of materials used have

led to many joining applications that would not be possible with more conventional join-

ing techniques. Adhesives are also being used either in conjunction with or to replace

5 For a more extensive discussion of this topic, see J. E. Shigley and C. R. Mischke, Mechanical Engineering

Design, 6th ed., McGraw-Hill, New York, 2001, Sec. 9–11. This section was prepared with the assistance of

Professor David A. Dillard, Professor of Engineering Science and Mechanics and Director of the Center for

Adhesive and Sealant Science, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, Virginia, and with

the encouragement and technical support of the Bonding Systems Division of 3M, Saint Paul, Minnesota.