Page 176 - Fluid Mechanics and Thermodynamics of Turbomachinery

P. 176

Axial-flow Compressors and Fans 157

Rotating stall and surge

A salient feature of a compressor performance map, such as Figure 1.10, is the limit

to stable operation known as the surge line. This limit can be reached by reducing the

mass flow (with a throttle valve) whilst the rotational speed is maintained constant.

When a compressor goes into surge the effects are usually quite dramatic. Gener-

ally, an increase in noise level is experienced, indicative of a pulsation of the air

flow and of mechanical vibration. Commonly, there are a small number of predomi-

nant frequencies superimposed on a high background noise. The lowest frequencies

are usually associated with a Helmholtz-type of resonance of the flow through the

machine, with the inlet and/or outlet volumes. The higher frequencies are known

to be due to rotating stall and are of the same order as the rotational speed of the

impeller.

Rotating stall is a phenomenon of axial-compressor flow which has been the

subject of many detailed experimental and theoretical investigations and the matter

is still not fully resolved. An early survey of the subject was given by Emmons

et al. (1959). Briefly, when a blade row (usually the rotor of a compressor reaches

the “stall point”, the blades instead of all stalling together as might be expected, stall

in separate patches and these stall patches, moreover, travel around the compressor

annulus (i.e. they rotate).

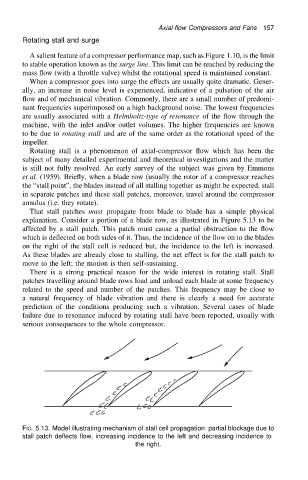

That stall patches must propagate from blade to blade has a simple physical

explanation. Consider a portion of a blade row, as illustrated in Figure 5.13 to be

affected by a stall patch. This patch must cause a partial obstruction to the flow

which is deflected on both sides of it. Thus, the incidence of the flow on to the blades

on the right of the stall cell is reduced but, the incidence to the left is increased.

As these blades are already close to stalling, the net effect is for the stall patch to

move to the left; the motion is then self-sustaining.

There is a strong practical reason for the wide interest in rotating stall. Stall

patches travelling around blade rows load and unload each blade at some frequency

related to the speed and number of the patches. This frequency may be close to

a natural frequency of blade vibration and there is clearly a need for accurate

prediction of the conditions producing such a vibration. Several cases of blade

failure due to resonance induced by rotating stall have been reported, usually with

serious consequences to the whole compressor.

FIG. 5.13. Model illustrating mechanism of stall cell propagation: partial blockage due to

stall patch deflects flow, increasing incidence to the left and decreasing incidence to

the right.