Page 244 - Low Temperature Energy Systems with Applications of Renewable Energy

P. 244

Geothermal energy in combined heat and power systems 231

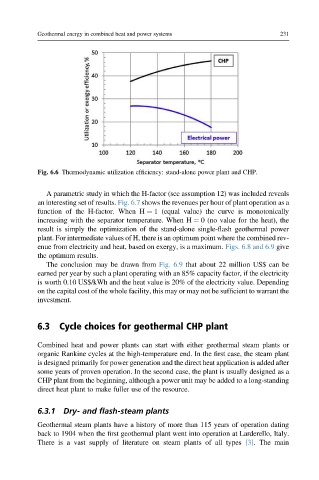

Fig. 6.6 Thermodynamic utilization efficiency: stand-alone power plant and CHP.

A parametric study in which the H-factor (see assumption 12) was included reveals

an interesting set of results. Fig. 6.7 shows the revenues per hour of plant operation as a

function of the H-factor. When H ¼ 1 (equal value) the curve is monotonically

increasing with the separator temperature. When H ¼ 0 (no value for the heat), the

result is simply the optimization of the stand-alone single-flash geothermal power

plant. For intermediate values of H, there is an optimum point where the combined rev-

enue from electricity and heat, based on exergy, is a maximum. Figs. 6.8 and 6.9 give

the optimum results.

The conclusion may be drawn from Fig. 6.9 that about 22 million US$ can be

earned per year by such a plant operating with an 85% capacity factor, if the electricity

is worth 0.10 US$/kWh and the heat value is 20% of the electricity value. Depending

on the capital cost of the whole facility, this may or may not be sufficient to warrant the

investment.

6.3 Cycle choices for geothermal CHP plant

Combined heat and power plants can start with either geothermal steam plants or

organic Rankine cycles at the high-temperature end. In the first case, the steam plant

is designed primarily for power generation and the direct heat application is added after

some years of proven operation. In the second case, the plant is usually designed as a

CHP plant from the beginning, although a power unit may be added to a long-standing

direct heat plant to make fuller use of the resource.

6.3.1 Dry- and flash-steam plants

Geothermal steam plants have a history of more than 115 years of operation dating

back to 1904 when the first geothermal plant went into operation at Larderello, Italy.

There is a vast supply of literature on steam plants of all types [3]. The main