Page 147 - Dynamic Vision for Perception and Control of Motion

P. 147

5.2 Efficient Extraction of Oriented Edge Features 131

size expected (domain knowledge) or known from previous images, thereby reduc-

ing the computational load.

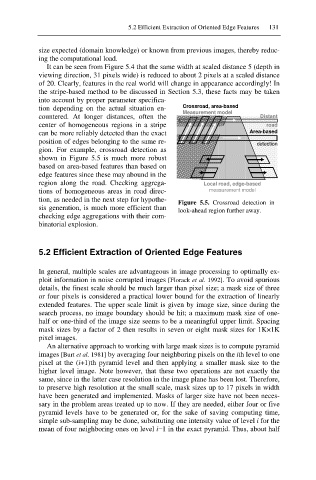

It can be seen from Figure 5.4 that the same width at scaled distance 5 (depth in

viewing direction, 31 pixels wide) is reduced to about 2 pixels at a scaled distance

of 20. Clearly, features in the real world will change in appearance accordingly! In

the stripe-based method to be discussed in Section 5.3, these facts may be taken

into account by proper parameter specifica-

tion depending on the actual situation en- Crossroad, area-based

Measurement model

countered. At longer distances, often the Distant

center of homogeneous regions in a stripe road

can be more reliably detected than the exact Area-based

position of edges belonging to the same re-

detection

gion. For example, crossroad detection as

shown in Figure 5.5 is much more robust

based on area-based features than based on

edge features since these may abound in the

region along the road. Checking aggrega- Local road, edge-based

tions of homogeneous areas in road direc- measurement model

tion, as needed in the next step for hypothe- Figure 5.5. Crossroad detection in

sis generation, is much more efficient than

look-ahead region further away.

checking edge aggregations with their com-

binatorial explosion.

5.2 Efficient Extraction of Oriented Edge Features

In general, multiple scales are advantageous in image processing to optimally ex-

ploit information in noise corrupted images [Florack et al. 1992]. To avoid spurious

details, the finest scale should be much larger than pixel size; a mask size of three

or four pixels is considered a practical lower bound for the extraction of linearly

extended features. The upper scale limit is given by image size, since during the

search process, no image boundary should be hit; a maximum mask size of one-

half or one-third of the image size seems to be a meaningful upper limit. Spacing

mask sizes by a factor of 2 then results in seven or eight mask sizes for 1K×1K

pixel images.

An alternative approach to working with large mask sizes is to compute pyramid

images [Burt et al. 1981] by averaging four neighboring pixels on the ith level to one

pixel at the (i+1)th pyramid level and then applying a smaller mask size to the

higher level image. Note however, that these two operations are not exactly the

same, since in the latter case resolution in the image plane has been lost. Therefore,

to preserve high resolution at the small scale, mask sizes up to 17 pixels in width

have been generated and implemented. Masks of larger size have not been neces-

sary in the problem areas treated up to now. If they are needed, either four or five

pyramid levels have to be generated or, for the sake of saving computing time,

simple sub-sampling may be done, substituting one intensity value of level i for the

mean of four neighboring ones on level ií1 in the exact pyramid. Thus, about half