Page 238 - Earth's Climate Past and Future

P. 238

214 PART IV • Deglacial Climate Change

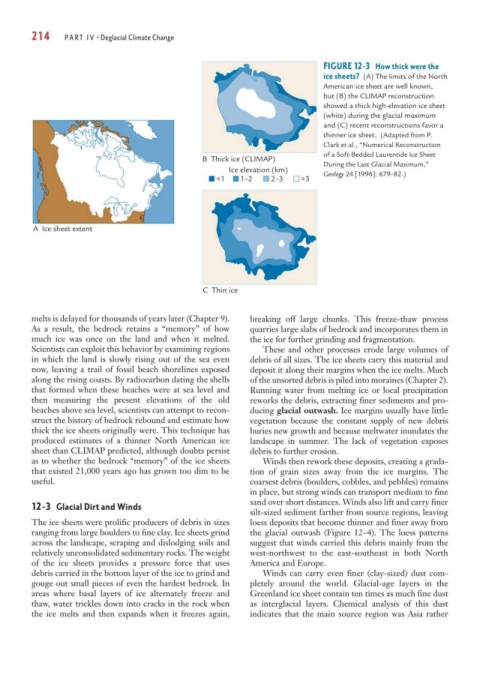

FIGURE 12-3 How thick were the

ice sheets? (A) The limits of the North

American ice sheet are well known,

but (B) the CLIMAP reconstruction

showed a thick high-elevation ice sheet

(white) during the glacial maximum

and (C) recent reconstructions favor a

thinner ice sheet. (Adapted from P.

Clark et al., “Numerical Reconstruction

of a Soft-Bedded Laurentide Ice Sheet

B Thick ice (CLIMAP)

During the Last Glacial Maximum,”

Geology 24 [1996]: 679–82.)

Ice elevation (km)

<1 1–2 2–3 >3

A Ice sheet extent

C Thin ice

melts is delayed for thousands of years later (Chapter 9). breaking off large chunks. This freeze-thaw process

As a result, the bedrock retains a “memory” of how quarries large slabs of bedrock and incorporates them in

much ice was once on the land and when it melted. the ice for further grinding and fragmentation.

Scientists can exploit this behavior by examining regions These and other processes erode large volumes of

in which the land is slowly rising out of the sea even debris of all sizes. The ice sheets carry this material and

now, leaving a trail of fossil beach shorelines exposed deposit it along their margins when the ice melts. Much

along the rising coasts. By radiocarbon dating the shells of the unsorted debris is piled into moraines (Chapter 2).

that formed when these beaches were at sea level and Running water from melting ice or local precipitation

then measuring the present elevations of the old reworks the debris, extracting finer sediments and pro-

beaches above sea level, scientists can attempt to recon- ducing glacial outwash. Ice margins usually have little

struct the history of bedrock rebound and estimate how vegetation because the constant supply of new debris

thick the ice sheets originally were. This technique has buries new growth and because meltwater inundates the

produced estimates of a thinner North American ice landscape in summer. The lack of vegetation exposes

sheet than CLIMAP predicted, although doubts persist debris to further erosion.

as to whether the bedrock “memory” of the ice sheets Winds then rework these deposits, creating a grada-

that existed 21,000 years ago has grown too dim to be tion of grain sizes away from the ice margins. The

useful. coarsest debris (boulders, cobbles, and pebbles) remains

in place, but strong winds can transport medium to fine

sand over short distances. Winds also lift and carry finer

12-3 Glacial Dirt and Winds

silt-sized sediment farther from source regions, leaving

The ice sheets were prolific producers of debris in sizes loess deposits that become thinner and finer away from

ranging from large boulders to fine clay. Ice sheets grind the glacial outwash (Figure 12–4). The loess patterns

across the landscape, scraping and dislodging soils and suggest that winds carried this debris mainly from the

relatively unconsolidated sedimentary rocks. The weight west-northwest to the east-southeast in both North

of the ice sheets provides a pressure force that uses America and Europe.

debris carried in the bottom layer of the ice to grind and Winds can carry even finer (clay-sized) dust com-

gouge out small pieces of even the hardest bedrock. In pletely around the world. Glacial-age layers in the

areas where basal layers of ice alternately freeze and Greenland ice sheet contain ten times as much fine dust

thaw, water trickles down into cracks in the rock when as interglacial layers. Chemical analysis of this dust

the ice melts and then expands when it freezes again, indicates that the main source region was Asia rather