Page 240 - Earth's Climate Past and Future

P. 240

216 PART IV • Deglacial Climate Change

Testing Model Simulations against The COHMAP researchers then ran model simula-

Biotic Data tions of climate at intervals of several thousand years

between the glacial maximum and the present to deter-

So far, we have examined only the physical aspects (ice mine how changes in the major boundary conditions

and dirt) of the glacial maximum world. But living drove regional patterns of climate change. The

organisms also have a story to tell. They also allow us to COHMAP team focused on the role of orbital-scale

test the performance of climate models on a world quite changes in climate over intervals of thousands of years,

different from ours. rather than on shorter-term fluctuations superimposed

on this gradual trend.

12-4 COHMAP: Data-Model Comparisons The climate data produced as output from these

model simulations were then tested against climate

During the 1980s, an interdisciplinary project called reconstructions using C-dated records of pollen from

14

COHMAP (Cooperative Holocene Mapping Project) lake cores and plankton shells from ocean sediment

used a combined data-model approach to examine the cores. Modern relationships between the abundances of

last glacial maximum and the subsequent changes to species and climatic variables can be measured, quanti-

interglacial conditions. Led by the meteorologists John fied, and used to reconstruct past climates from fossil

Kutzbach and Tom Webb, the paleoecologist Herb organisms. By comparing these fossil-based estimates of

Wright, and the geographer Alayne Street-Perrott, climate with the changes simulated by the models,

COHMAP brought together scientists from countries scientists can test the reliability of both approaches (see

around the world to pool information from hundreds of Figure 12–6).

individual C-dated records of lake levels and pollen

14

in lake sediments for the purpose of examining regional-

scale patterns. 12-5 Pollen: An Indicator of Climate on the

The first step in the COHMAP approach was to Continents

assemble records of the changing boundary conditions

that have driven climate over the last 21,000 years Precipitation and temperature determine the larger-

(Figure 12–6). As noted earlier, the largest differences scale vegetation units such as forests, grasslands, and

in boundary conditions compared to conditions today deserts and also the distribution of particular species

were the larger ice sheets and the lower greenhouse-gas within those units. Pollen is carried mainly by winds

concentrations (see Figure 12–1). and to a lesser extent by water and insects. Some pollen

comes to rest in lakes and settles into the mud, where its

resistant outer layer aids preservation. The preserved

pollen reflects the average composition of vegetation

over a region extending tens of kilometers from the

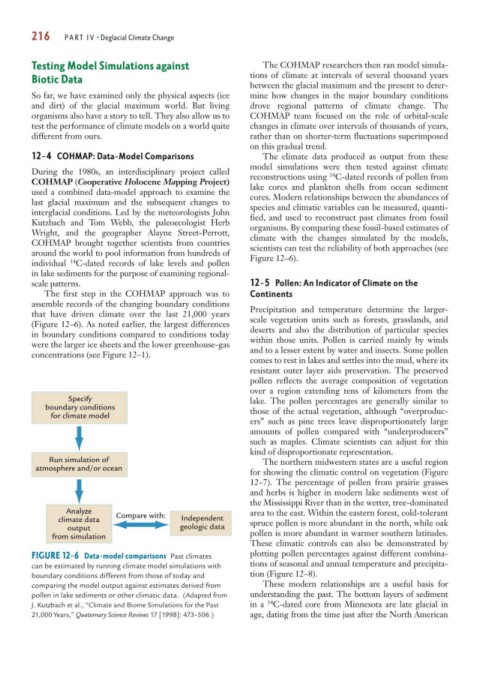

Specify lake. The pollen percentages are generally similar to

boundary conditions those of the actual vegetation, although “overproduc-

for climate model

ers” such as pine trees leave disproportionately large

amounts of pollen compared with “underproducers”

such as maples. Climate scientists can adjust for this

kind of disproportionate representation.

Run simulation of The northern midwestern states are a useful region

atmosphere and/or ocean

for showing the climatic control on vegetation (Figure

12–7). The percentage of pollen from prairie grasses

and herbs is higher in modern lake sediments west of

the Mississippi River than in the wetter, tree-dominated

Analyze area to the east. Within the eastern forest, cold-tolerant

climate data Compare with: Independent spruce pollen is more abundant in the north, while oak

output geologic data

from simulation pollen is more abundant in warmer southern latitudes.

These climatic controls can also be demonstrated by

FIGURE 12-6 Data-model comparisons Past climates plotting pollen percentages against different combina-

can be estimated by running climate model simulations with tions of seasonal and annual temperature and precipita-

boundary conditions different from those of today and tion (Figure 12–8).

comparing the model output against estimates derived from These modern relationships are a useful basis for

pollen in lake sediments or other climatic data. (Adapted from understanding the past. The bottom layers of sediment

14

J. Kutzbach et al., “Climate and Biome Simulations for the Past in a C-dated core from Minnesota are late glacial in

21,000 Years,” Quaternary Science Reviews 17 [1998]: 473–506.) age, dating from the time just after the North American